Read 1492: The Year Our World Began Online

Authors: Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

1492: The Year Our World Began (11 page)

Ethiopia, however, had already overreached its potential as a conquest state. Pagan migrants permeated the southern frontier. Muslim invaders pressed from the east, building up the pressure until within a couple of generations they threatened to conquer the highlands. Ethiopia barely survived. The frontier of Christendom began to shrink.

Meanwhile, beyond Ethiopia, the east coast of Africa was accessible to Muslim influence but cut off from that of Christians. In the sixteenth century the sea route around the Cape of Good Hope brought Portuguese merchants, exiles, and garrisons to the region. Here, however, Christianity never had the manpower or appeal to compete with Islam, while the inland states remained largely beyond the reach of missionaries of either faith.

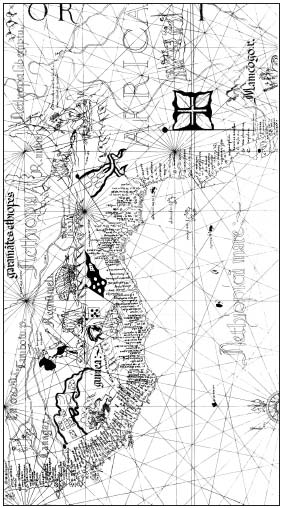

Diogo Homem’s map of West Africa (1558) shows São Jorge da Mina (topped with five-dotted flag), indigenous slave-raiding, and the ruler of Songhay, extravagantly behatted.

Diogo Homem’s map of West Africa from J. W. Blake,

Europeans in West Africa

,

I

(London, 1942). Courtesy of The Hakluyt Society.

The greatest of these states were at the far end of the Rift Valley, around the gold-strewn Zambezi. The productive plateau beyond, which stretched to the south as far as the Limpopo River, was rich in salt, gold, and elephants. Like Ethiopia, these areas looked toward the Indian Ocean for long-range trade with the economies of maritime Asia. Unlike Ethiopia, communities in the Zambezi Valley had ready access to the ocean, but they faced a potentially more difficult problem. Their outlets to the sea lay below the reach of the monsoon system and, therefore, beyond the normal routes of trade. Still, adventurous merchants—most of them, probably, from southern Arabia—risked the voyage to bring manufactured goods from Asia in trade for gold and ivory. Some of the most vivid evidence comes from the mosque in Kilwa, in modern Tanzania, where fifteenth-century Chinese porcelain bowls—products Arabian merchants shipped across the whole breadth of the ocean—line the inside of the dome.

Further evidence of the effects of trade lie inland, where fortified, stone-built administrative centers—called “zimbabwes”—had been common for centuries. In the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the zimbabwes entered their greatest age. The most famous, Great Zimbabwe, included a formidable citadel on a hill 350 feet high, but remains of other citadels are scattered over the land. Near stone buildings, the beef-fed elite were buried with gifts: gold, jewelry, jeweled ironwork, large copper ingots, and Chinese porcelain.

In the second quarter of the fifteenth century, the center of power shifted northward to the Zambezi Valley, with the expansion of a new regional power. Mwene Mutapa, as it was called, arose during the northward migration of bands of warriors from what are now parts of Mozambique and KwaZulu-Natal. When one of their leaders conquered the middle Zambezi Valley, he took the title Mwene Mutapa, or “lord of the tribute payers”—a name that became extended to the state. From about the mid–fifteenth century, the pattern of trade routes altered as Mwene Mutapa’s conquests spread eastward toward the coast. But Mwene Mutapa never reached the ocean. Native merchants, who traded

at inland fairs, had no interest in a direct outlet to the sea. They did well enough using middlemen on the coast and had no incentive for or experience of ocean trade. The colonists were drawn, not driven, northward, though a decline in the navigability of the Sabi River may have stimulated the move.

The events of 1492 hardly affected the remote interior and south of Africa. But the death of Sonni Ali Ber in the waters of the Niger, the consolidation of Portuguese influence that followed the baptism of Nzinga Nkuwu in Kongo, and the renewal—which was going on at about the same time—of Ethiopia’s diplomatic contact with the rest of Christendom were decisive events in carving the continent between Islam and Christianity. With Askia Muhammad’s triumph in Songhay, the accession of Afonso I in Kongo, and the success of Pedro de Covilhão’s mission to Ethiopia, the configurations of the religious map of Africa today—where Islam dominates across the Sahara and in the Sahel, as far as the northern forest belt, and along the Indian Ocean coast, with Christianity preponderant elsewhere—became, if not inevitable, highly predictable.

May 1: The royal decree expelling unbaptized Jews

from Spain is published.

T

here was not a Christian who did not feel their pain,” reported Andrés de Bernáldez, priest and chronicler, who watched the crowds of Jews making their way into exile from Castile in the summer of 1492. Making music as they went, shaking their tambourines and beating their drums to keep their spirits up, “they went by the roads and fields with great labor and misery, some falling, some struggling again to their feet, others dying or falling sick.” When they saw the sea, “they uttered loud screams and wailing, men and women, old and young, begging for God’s mercy, for they hoped for some miracle from God and that the sea would part to make a road for them. Having waited many days and seen nothing but trouble, many wished they had never been born.” Those who embarked “suffered disasters, robberies, and death

on sea and on land, wherever they went, at the hands of Christians and Moors alike.” Bernáldez knew “no sight more pitiable.”

1

Despite this avowal of compassion, Bernáldez hated Jews. By contumaciously refusing to recognize their Messiah, they had forfeited to Christians their heritage as God’s chosen people. The roles in the book of Exodus were now reversed: the Jews were the “evil, unbelieving idolaters,” and Christians were “the new children of Israel.” Bernáldez hated Jews for their arrogance in claiming God’s special favor. He hated the stink he scented on their breath and in their homes and synagogues, and which he attributed to the use of olive oil in cooking—for, amazing as it seems to anyone familiar with Spanish cooking today, medieval Castilians eschewed olive oil and used lard as their main source of dietary fat. He hated them with hatred born of economic envy, as dwellers “in the best locations in cities and towns and the choicest, richest lands” and as work-shy capitalists who “sought prosperous occupations, so as to get rich with little work,…cunning people, who usually lived off the many extortions and usuries they gained from Christians.”

2

He hated them, above all, for their privileges. Jews were exempt from tithes and, if they lived in their own ghettoes (which by no means all did), were not obliged to pay municipal taxes. They elected the officials of their own communities. They enjoyed their own jurisdiction, and until 1476 they regulated their own business affairs among themselves according to their own laws. Even after that date, lawsuits between Jews were settled outside the common legal system, by judges specially appointed by the crown. The Inquisition—the tribunal everyone else feared—could not touch them unless they were suspected of suborning Christians or committing blasphemy. Because their own customs allowed higher rates of interest than those chargeable under Christian law, they had an advantage in any form of business that involved handling debt. They farmed taxes and occupied positions of profit in royal and seigneurial bureaucracies—though diminishingly so by the late fifteenth century. They lived—in many cases—as tenants and protégés of church, crown, or aristocracy. Most Jews, of course, were poor arti

sans, small tradesmen, or laborers, but Bernáldez observed what we would now call a trickle-down effect, with the wealthy members of the community supporting the less fortunate. In that respect, Jews were a typical group in medieval society—an “estate” that transcended class, with fellow feeling and a sense of common interest uniting people at different levels of wealth and education in defense of their shared identity and collective privileges.

“Jew” became a term of abuse. Terms of abuse are rarely used literally. Nowadays “fascist” is an insult hurled undiscriminatingly at people who have no resemblance to fascists. “Liberal” is fast becoming a similarly unspecific term in the United States. Few of the people foulmouthed as “motherfuckers” in gangland parlance actually practice incest. Of most of the people denounced as Jews in fifteenth-century Spain, there is no independent evidence to connect them with Jewish ancestry, culture, or beliefs. If the term meant anything, it seems to have meant something like “thinking in an allegedly Jewish way”—which meant, in practice, thinking pharisaically: having, for instance, a literal-minded attitude to the law, or being more concerned with material or legalistic values than with spirituality. Of course, these thought patterns were not genuinely Jewish—you can find them in people of all religions and none—but readers of the letters of St. Paul would recognize them as the sort of thoughts the apostle regarded as un-Christian.

Anti-Semitism is so perversely irrational that it is hard for any clearheaded person to understand. Christians, especially, ought to be immune to its venom, because their religion originated in Judaism and owes much of its doctrine, ritual, and scripture to the Jewish past. Christ, his mother, and all the apostles were Jews. The good that Jews have done the world by way of science, art, literature, and scholarship has been out of all proportion to their numbers. No community of similar size can rival Jews for the blessings they have brought the rest of us. Yet any conspicuous minority—and Jews have always formed conspicuous minorities—seems to ignite prejudice and attract odium. Privileged minorities stoke hatred even more intensively. And though

Christianity did not cause anti-Semitism, which was rife in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds before Christ, it provided a new pretext. Mobs regularly plundered Jews when readings in church reminded them that Christ’s co-religionists demanded his crucifixion and cried, “His blood be upon us and on our children!”

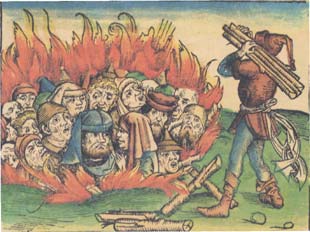

Hartmann Schedel, the principal author of the Nuremberg Chronicle, collected Hebrew books, perhaps in the hope of sparing them from the burning he anticipated as a harbinger of the imminent end of the world.

Nuremberg Chronicle.

In a notorious case heard in ávila in 1491, on evidence recorded by hearsay or extracted by torture, Jews and some former Jews were condemned for crucifying a child, with a lot of mocking mummery of Christ’s crucifixion, and eating his heart in a parody of the mass, as well as stealing and blasphemously abusing a consecrated Host for purposes of black magic. The allegedly murdered child—never convincingly named, never produced—probably never existed, but he became the hero of sensationalist literature, the object of a popular cult, and the genius of a shrine that attracts worshippers to ávila to this day. The

supposed perpetrators of the crimes were garroted, or dismembered with red-hot pincers, and their grisly remains were burned so as not to pollute the earth. The Inquisition gave the case a huge billing. Much of it was heard in the presence of the Grand Inquisitor himself, and the findings—suitably massaged to conceal the implausibility of most of the charges and the contradictions of most of the testimony—were lavishly publicized. Some of the most learned jurists in Spain endorsed the sentence, despite the outrageous deficiencies of the evidence.

The case revealed three troubling aspects of the deteriorating reputation of Jews in the kingdom. First, public credulousness was an index of how far anti-Semitism had penetrated the culture. Second, the imagery of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross and in the Eucharist, despite Christians’ moral debt to Judaism, could easily be twisted into service against Jews. Finally, the trial seems, in retrospect, obviously contrived to serve political ends. By showing Jews and former Jews colluding in ritual murder and black magic, the inquisitors managed to establish in policy makers’ minds a suppositious link between Judaism and Christian apostasy.

For what really worried the partisans of expulsion of the Jews was that, while Jewish communities remained in place, converts from Judaism could not escape the corroding effects of a Jewish environment. In the La Guardia case, the only charge that was proved against one of the alleged conspirators was that

not content with the fact that, for humanity’s sake alone, as our holy faith prescribes, he, together with all other Jews, has the right to consort and converse with faithful Catholic Christians, he seduced certain Christians to his damnable law with false and deceitful preachings and suggestions, as a fautor of heresy, saying and expounding to them that the law of Moses was the only true law, in which they must be saved, and that the law of Jesus Christ was a feigned and dissembled law, never imposed or established by God.

3

It was therefore the policy of the Inquisition to insulate society from Jewish influence. It was also a popular cause. The result of free association between Christians and Jews, according to Bernáldez, who was dim enough to be representative of popular prejudices, was that converts from Judaism and their descendants tended to be either “secret Jews” or “neither Jews nor Christians”—“like Muhammad’s beast of burden, neither horse nor mule,” as a tract of 1488 said.

4

Rather, they were godless antinomians who withheld their children from baptism, respected no fasts, made no confession, and gave no alms, but lived for gluttony and sexual excess or, in the case of backsliders into Judaism, ate Jewish food and observed Jewish customs.

There was probably some truth in the less sensational of these accusations: in a culturally ambiguous, transgressive setting, people can easily transcend traditions, escape dogma, and create new synergies. Investigations by the Inquisition uncovered many cases of religious indifference or outright skepticism. The late-fifteenth-century convert Alfonso Fernández Semuel asked to be buried with a cross at his feet, a Quran on his breast, and a Torah “high on his head”—as we know from a satire denouncing him for behaving crazily.

5

A sophisticated Jewish convert who became a bishop and a royal inquisitor felt that “because converts from Judaism are learned and intelligent, they cannot and will not believe or engage in the nonsense believed and diffused by Gentile converts to Catholicism.”

6

In areas where Jews were relatively numerous, their practices infected culture generally. “You should know,” Bernáldez asserted, “that the habits of the common people, as the Inquisition discovered, were no more nor less than those of the Jews, and were steeped in their stench, and this was the result of the continual contact people had with them.”

Anti-Semitism was part of the background that makes the expulsion of the Jews intelligible, but it was not its cause. Indeed, Iberia tolerated its Jews for longer than other parts of western Europe. England expelled its Jews in 1291, France in 1343, and many states in western Germany followed suit in the early fifteenth century. The big problem of the ex

pulsion is not why it happened, but why it happened when it did. Money grubbing was not the motive. By refusing a bribe to abrogate the decree of expulsion, the monarchs of Castile and Aragon surprised the Jewish leaders who thought the whole policy was simply a ruse to extort cash. The Jews were reliable fiscal milch-cows. By expelling those who worked as tax gatherers, the monarchs imperiled their own revenues. It took five years for returns to recover their former levels. The Ottoman sultan Suleiman I is said to have marveled at the expulsion because it was tantamount to “throwing away wealth.”

7

“We are astonished,” the king wrote in self-vindication to one opponent of the expulsion,

that you should think we want to take the Jews’ possessions for ourselves, for that is very far from our thoughts…. While we want to recover for our court, as is reasonable, all that rightfully belongs to us by way of debts the Jews owe in taxes or other dues owed by their community, once their debts to us and other creditors have been paid, what remains should be returned to the Jews, to each his own, so that they may do as they wish with it.

8

The monarchs seem to have been entirely sincere in their determination not to profit from the expulsion: to them, it was a spiritual purgation. Synagogues were seized for conversion into churches, almshouses, and other public institutions, and cemeteries were generally turned over to common grazing; but other Jewish communal property was assigned to be held in escrow for settlement of Jews’ debts, which, in theory, were recoverable by Christian and Jewish creditors alike. Jews could realize the value of their assets in cash and, by a modification of the original decree of expulsion, take the proceeds abroad with them, together with unlimited movable wealth in the form of jewels, bonds, and bills of exchange. This was a remarkable concession, as the laws of the realms of Aragon and Castile were strict about absolutely prohibiting the export of money and valuables. Some exceptions were even granted for the removal of bullion: the leading figure among the

expulsees, Isaac Abranavel, was allowed ten thousand ducats in gold and jewels. Probably no more than a dozen individuals in the entire kingdom could lay their hands on that much cash.

In every diocese, the monarchs appointed administrators to look after personal property that Jews left unsold at the expulsion and, when its value could be realized, to pay the proceeds to the expulsees in their new homes abroad, and to recover and remit unpaid debts owed to expelled Jews. Some of these administrators labored for years at the job, with mixed results, and their records show how evil some of the unintended consequences were. Buyers extorted property from desperate expulsees. Municipalities acted illegally in seizing Jews’ assets and used every imaginable form of prevarication to avoid disgorging them. In a buyers’ market, it was impossible to get a fair price for Jewish property. Rapacious officials robbed exiles of cash or extorted unlawful bribes or illegal fees. Debtors to Jewish creditors evaded their obligations. Freighters overcharged. Despite honest efforts by administrators the crown appointed, most wrongs were probably never righted. The entire process was ill thought out, and the monarchs had simply not allowed enough time for all the problems to be solved before the Jews were made to leave.