Read Nabokov in America Online

Authors: Robert Roper

Nabokov in America (8 page)

Three years later, Nicolas declined an invitation to visit with Wilson, saying that he was about to leave for California, where he would spend ten days with Stravinsky:

It occurred to me

38

that I might try to write something on Stravinsky of a kind Niccolo Tucci wrote on Einstein. Do you think, if well done, it could suit the New Yorker for the “Reporter at Large” column?—It is my first trip to California. I am going with Balanchine.

Wilson replied, “I have taken your suggestion up with them here … and they say they would like to see [a Stravinsky article]. They can’t promise anything … but I think it would be worthwhile to submit it.”

Two years later, when his first book appeared, Nicolas made sure an advance copy got to Wilson:

I hope

39

(so much) that

you

will review it for The New Yorker… . It would give me such a pleasure. The fact [is] I not only hope that you

will

review it, but think that you “must” review it (as a teacher “must” review the papers of his students) because you are the godfather of the book insofar as it was you who started me on the “pay the way by writing” career. Will you? Will you

please

?

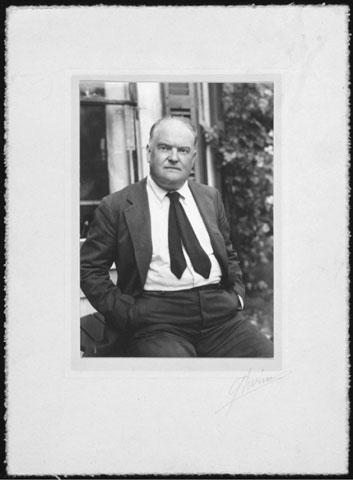

Whether or not this experience made Wilson cautious about helping other writers named Nabokov, the meeting with Vladimir took place in October 1940, and it proved a success. The men had a Mutt and Jeff radical difference physically, but in other respects they were reflections: literary out to their fingertips; contentious know-it-alls; sons of upper-class families, their fathers distinguished jurists involved in politics; lovers of Proust, Joyce, Pushkin. Both had struggled and would continue struggling to make a living by their pen. Wilson, then at the

New Republic

, offered Nabokov books to review, and the explosive material of dangerous future arguments was immediately before them: reviewing a book called

The Guillotine at Work

, by G. P. Maximoff, about the Soviet Union, Nabokov wrote,

The seven years

40

of Lenin’s regime cost Russia from 8 to 10 million lives; it took Stalin ten years to add another 10 million, thus, according to Mr. Maximoff’s “very conservative estimate,” between 1917 and 1934 there perished about 20 million people, some being tortured and shot, others dying in prisons, others again falling in the Civil War… . The appearance of this tragic and terse book is especially welcome because it may help to dispose of the wistful myth that Lenin was any better than his successor.

Wilson,

in

To the Finland Station

, argued that Lenin was indeed better, was an indispensable man, in fact, bearer of the torch of history’s oppressed. At a dinner at Roman Grynberg’s,

‡

Nabokov expressed a lesser estimation of the dictator, which prompted Wilson to send him a copy of his new book “

in the hope

41

that this may make [you] think better of Lenin.” The attractions of authentic friendship must already have been strong between them, not to mention Nabokov’s awareness of the

impolitique

of offending the foremost literary critic in America. Vladimir did not explode, or go off on a contemptuous rant, as at other times he did when encountering American beliefs about Lenin; on the subject of Soviet rulers, he was an absolutist, disinclined to see anything attractive or inspiring in the extermination of millions and the smothering of a liberal alternative in the catastrophe of 1917. Loyalty to his father’s memory was part of his anti-Bolshevism (which over the years came to resemble garden-variety American anti-Communism, with, in the fifties, a bemused fondness for Joe McCarthy, and in the sixties outright disgust with long-haired American students protesting the war in Vietnam). Loyalty to his own hopes in America, too, was a factor. Already he was aware that Russians of the emigration—the million-plus people who had been driven out or had fled after the Revolution— were illegitimate as a class, in the eyes of many educated Westerners. If they were anti-Soviet, they must be reactionary, the thinking went; if they condemned the events of 1917, they were standing in the way of history.

Wilson was not a propagandist for Stalin or even Lenin. By the time he finished

Finland Station

, he was in horror of the purge trials and the frenzy of political murders, and he

noted in a letter

42

that his writing of

Finland Station

was ending just as Russia was trying to end Finland (in the Russo-Finnish War). Wilson had been shaped by the Depression, which he reported for the

New Republic

. After a professional beginning on the cultural side, he became more interested in social issues, responding to the Crash with a feeling of deep anxiety for his beleaguered country:

There are today

43

[January 1931] in the United States … something like nine million men out of work; our cities are scenes of privation and misery on a scale which sickens the imagination … our agricultural life is bankrupt … our industry, in shifting to the South, has reverted almost to the horrible conditions … of the England of a hundred years ago.

A “darkness” had descended, Wilson felt, bringing a sense of “

a rending

44

of the earth in preparation for the Day of Judgment.” He paid particular attention to the epidemic of American suicides. This bespoke an enfeeblement of will, although his feeling toward suicides was entirely compassionate. He gave up his literary portfolio at the

New Republic

to travel the country for many months, writing about factory politics and Henry Ford as an incoherent prophet of capitalism; about starvation in plain sight; about the trial of the Scottsboro Boys in Chattanooga. In ’32, he assembled

his reportage

45

in a book called

The American Jitters: A Year of the Slump

, a largely nondoctrinaire, upsetting, meticulously reported account of the deep wound to American prospects. In a chapter called “The Case of the Author,” he offered a bluff self-profile: petit-bourgeois, conventional, pleasure-seeking, selfish. He

reported his earnings

46

during the twenties, noting that family money had afforded him leisure time for “reading, liquor, and general irresponsibility.”

Part of Wilson’s attraction to Soviet Communism came from a feeling that the American people were being poorly served. With a businessman’s president in the White House, there had been a shocking failure to recognize the near abyss; this same president “

kept telling us

47

,” Wilson wrote, “that the system was perfectly sound,” and meanwhile he sent General Douglas MacArthur “to burn the camp of the unemployed war veterans who had come to appeal … [and] we wondered about the survival of republican American institutions.” The Soviets did not blink at such profound problems, Wilson felt—they grabbed them by the throat. “We became

more and more impressed

48

by the achievements of the Soviet Union, which could boast that its industrial and financial problems were carefully studied by the government, and that it was able to avert such crises.”

By the time of his first meeting with Nabokov, Wilson had wised up considerably about the Soviets, especially about Stalin. In 1935 he traveled to Russia on a Guggenheim, and his prolific energy and capacity for meeting people and getting their story gave him material for three books. In Russia he was aware of the police state, of the active

fear among intellectuals, many soon to be executed; the crowds on the streets seemed “

dingy

49

” and “monotonous,” and socialism had not cured an overriding Russian sadness, he felt—quite the contrary. Still, Wilson did not forefront the fear in the books he wrote; instead he looked for elements of the Soviet story that might translate into an American

idiom, that signaled competence, a grip on the future. The two lands were comparable, after all: both were vast, both still untamed, all “

prairies and wild rivers

50

and forests,” and “we never know what we have got in the … wastes of these countries; we never know what is going to come out of them.”

*

Nabokov’s father was himself an enthusiastic chaser of moths and butterflies. In Nabokov’s novel

The Gift

, his hero, Fyodor, considers writing a biography of his late father, an eminent field scientist, and his account of his father’s adventures in western China has a grand, heartfelt style—the contemplation of a lost father, a daring naturalist, relieves him of his customary irony, is an opening to deep feeling. At the time of Nabokov’s arrival, the American Museum was headed by Dr. Roy Chapman Andrews, a naturalist-explorer much in the mold of Fyodor’s adventurous father. Andrews as a young man had so desired to work at the AMNH that, upon being denied a scientific job, he went to work as a janitor in the taxidermy department.

†

Wilson was not a sportsman. As a boy he gave away the baseball outfit his mother had bought him in hopes that it would encourage him to be athletic, and by the time Nabokov got to know him he was notably short, stout, and gouty. Nevertheless, Nabokov hoped to recruit him for collecting. “Try, Bunny,” he wrote, addressing Wilson by his nickname. Chasing butterflies “is the noblest sport in the world.”

‡

Wilson knew Grynberg independently of Nabokov, who had been his English tutor in France. Grynberg was a book-loving businessman deeply saturated in literature, a publisher of Russian-language journals after his move to the United States. His sister Irina had become a friend of Wilson’s while serving as his guide in Moscow in 1935, when Wilson was reporting his book

Travels in Two Democracies

(’36).

With

Wilson getting him review assignments and making many contacts for him, Nabokov was able to survive his first winter in America without a steady job. There was the Stanford position to look forward to, and cousin Nicolas arranged a lecture for him at upstate Wells College in February. Nabokov had arrived in the United States with “

one hundred lectures

1

—about 2,000 pages—on Russian literature” already prepared and ready to be rolled out should opportun- ities arise. He saw himself as a professor-to-be as well as an artist—saw himself delivering cultural goods, knowledge of an exotic foreign literature, to a deprived audience willing to pay for it. His hopefulness was not misplaced, and his immigrant’s adaptive strategy was a good one.

Karpovich of Harvard recommended him to a booking service, and Wellesley College invited him for two weeks of talks in March ’41, partly because a copy of

his 1922 translation

2

of

Alice in Wonderland

was among the library’s Lewis Carroll editions. He proved a seductive, roaringly funny, erudite, and becomingly accented lecturer in English. “My lectures are

a purring success

3

,” he wrote Wilson. “Incidentally I have slaughtered Maxim Gorky, Mr. Hemingway—and a few others.” He liked the Wellesley girls and also the “very charming” women professors, and while in Boston he had lunch with Edward Weeks, who, like Nabokov, had attended Trinity College, Cambridge. Weeks “received my story and me with very touching warmth,” he reported—the story, “Cloud, Castle, Lake,” was one that Wilson had recommended— and Weeks followed up with such praise (“this is genius”) and so unconditional an invitation to further submissions to the

Atlantic

(“this is what we have been looking for”) that Nabokov was shocked.

Véra

was ill for much of the year, underweight and suffering “

from all the migrations

4

and anxieties,” as she later described it. She looked for work, found it in January ’41—translating for a Free French newspaper—and lost it when laid up for weeks with

sciatica

5

. Her troubled back threatened the planned trip to Palo Alto: it seemed unlikely she would be able to travel, but on May 26, a Monday and also the day of a new moon, the family set out for the West, in the car belonging to Dorothy Leuthold, one of Vladimir’s language students.

To drive to California in ’41 was to go adventuring, in a small way. The

system of numbered

6

roads (U.S. 1, Md. Hwy 97) was only about ten years old, and many roads, including major routes, were still poorly surfaced. The world context, meanwhile, was unstable in the extreme. Two weeks before they left, in the heavy American car containing manuscripts and a seven-year-old,

3,600 Jews

7

had been rounded up in Paris by the Gestapo, many of them children.

The Germans had just captured Crete, and their warships were decimating British shipping in the North Atlantic. German intentions vis-à-vis the Soviet Union, its Non-Aggression Pact partner, were showing a new character. To what extent Nabokov or his wife monitored events by newspaper or radio is hard to know, but Vladimir observed in a letter to Wilson after the German attack in the east,